Adirondack Loon Blog

Enjoy our reports of rescues, visits with loons, and other adventures in the Adirondacks!

4/8/24: Total Eclipse with a Loon

At 2:00 PM on April 8, 2024, I packed my twelve-foot canoe with gear and cameras and paddled out onto Paradox Lake to witness the total eclipse of the sun. I hoped to observe how the wildlife and especially the loons, which had just returned to the iced-out lake, would react to the sudden, premature darkening of the sky. I had a camera with a 400 mm lens equipped with a home-made solar filter to photograph the sun itself, a camera with an 18-55mm lens for scenery, my cell phone camera, and of course, eclipse glasses. I was very excited.

I took a photo of the full sun for practice, and I could see two darker spots, probably sunspots, on the surface of the sun. The high, thin clouds made the image just a little fuzzy at times but were not a major problem. I waited a few minutes and looked through the big lens again and was thrilled to see a tiny flat spot at the lower right edge of the sun. The eclipse was starting!

My neighbors were sitting on their deck overlooking the lake and we waved to each other. People were scattered around the shore at private camps, beaches, and the state campground to enjoy this rare experience. One other kayak was out near the campground, but my canoe was the only other craft on the upper lake. The winds were light, the water fairly calm, and the warm, sunny afternoon was quiet except for the call of a merlin. Now I had to find a loon.

I searched with binoculars and located Scruffy, a new male loon who was trying to establish a territory in the inlet cove. I had watched him interact with the eastern loon pair the previous day when these loons had just arrived from migration. Scruffy earned his name because he had not yet molted into full breeding plumage and had a slightly patchy appearance.

Every few minutes I looked at the sun through the camera lens and photographed. The moon seemed to be moving in front of the sun faster than I expected. I paddled down to the inlet cove to watch Scruffy, who was busy fishing. He was not nervous with my presence, and I watched him catch two small food items and then a fish that may have been a five-inch sunfish. Meanwhile, I photographed the sun and listened for birds and wildlife. It was rather quiet, and soon the moon was about halfway across the sun.

Then leopard frogs started calling from the inlet marsh. Scruffy stopped fishing and began to swim west toward the middle of the lake. I thought I could tell that daylight was diminishing ever so slightly. I followed Scruffy and when he reached the middle, he began to preen his feathers. Now I could tell that the sky was a bit darker, and apparently Scruffy could, too. He tucked his head under the feathers on his back and started to snooze. I drifted close to him, photographing with the regular lens. The south shoreline where my home is located, and the trees on Crawford Island, began to look darker.

Scruffy picked up his head, and slowly swam northwest toward Crawford Island. The sky looked strange, the blue becoming a darker dusky blue everywhere. I followed Scruffy from a distance, not wanting to influence where he went. Fish started rising and jumping. The air chilled, and I put on a hat and jacket. The wind died completely, and the lake went flat calm. The sky began to look blackish, yet there was still light around the horizon.

Scruffy let out a wail. I suddenly felt a wave of uneasiness, feeling small and vulnerable in a little canoe in the middle of a big lake that was maybe 34 degrees and about to be dark as night. I took a photo of the very thin sliver of the sun that was not yet blocked by the moon and started to paddle fast toward Crawford Island for the security of a shoreline. As I neared the northwest shore of Crawford, a chorus of cheers erupted from a group of folks watching the eclipse from Glen Reay’s Beach. I set the paddle down fast, and looked at the sun, now a small white ring of totality in a black night sky.

I tried to photograph the sun with my telephoto lens, but the solar filter blocked out what little light could edge around the moon. I picked up my regular camera and tried to capture the incredible scene: black sky with a white ring for a sun up high, then deep blue shading to medium blue with some thin clouds, with white and gold light near the horizon. It was not quite as dark as full night due to the lighter horizon sky that reflected off the water. The landscape was surreal, unlike any sunset or sunrise I had ever witnessed.

I gawked with my eyes alone and took as many photos of the sun and the landscape with my regular camera as I could. Suddenly a speck of intense light, the “diamond ring” appeared at the edge of the sun. In seconds the speck grew, light shone back down onto the earth like a spotlight, and the sun became too bright to look at without eclipse glasses. Dawn came faster than a peregrine falcon.

The birds responded immediately, just as if the sun had risen at 6:20 AM. Robins sang, and pine siskins, goldfinches, and purple finches started up their chatter. The eastern loon pair swam into view, heading east, patrolling their territory. They hooted, most likely looking for Scruffy to drive him away. Scruffy dove and swam underwater a long way and kept his distance.

I took off my hat and jacket as the air temperature warmed. The wind picked up, and a slight chop developed on the water. Paddling along the island’s shore, I continued to photograph the moon moving upward across the surface of the sun. I noticed the silhouettes of white pine and cedar branches against the orange glow of the sun and photographed them. By now the loon pair had turned back west, and I noticed Scruffy way down in the inlet cove where I had first found him when the eclipse began.

Continuing to photograph every few minutes until the moon was once again just a tiny flat spot at the top of the sun, I paddled toward our shore. What an unforgettable experience! It was surreal, moving, and profound, and I felt connected to the earth, the moon, and the sun as never before. I have always felt bonded to the animals and plants of the earth, but now I feel like a child of the universe.

~E. George, ACLC Field Staff & Loon Naturalist Extraordinaire

10/17/23: “Loon Pond,” NY - Visitors at Loon Pond

On October 17, two loons were present on Loon Pond, but only one of them was an adult. The second loon was a juvenile. But wait! The territorial loon pair nested this summer, but their nest was predated late in incubation, and they did not have any chicks this year. Where did this youngster come from? Neither of the closest ponds had nesting loons this year. This first year bird must have come from a pond or lake a few miles or more distant. It was fairly tolerant of me in my canoe, which suggests that perhaps it was raised on a lake with a strong human presence and lots of boats and was accustomed to them.

The juvenile was interested in the adult and swam toward it, but the adult dove and kept its distance, seeming to try to avoid interacting with the juvenile. The adult was probably the territorial male because it was molting heavily into winter plumage and the male usually stays on this pond longer than the female before migrating. However, I was not able to see the bands on its legs, so I do not know for sure. It is interesting that the territorial adult did not try to drive off this juvenile, who was not its own chick. The adult spent most of its time fishing and dove frequently, while the juvenile swam on the surface and watched the adult, following it from a distance.

The next time I visited Loon Pond was November 3rd, and I did not expect any loons to be left on the pond. I was right. But in November, Loon Pond becomes Merganser Pond, as numbers of migrating common and hooded mergansers stop by and feed. One male common merganser was by itself, and it took flight, circling the pond and heading west. At least 25 hooded mergansers were feeding, and they were in two groups. One group had two males and three females, and the other group had about 20 females and juveniles.

When I tried to get closer for photographs, they took flight and flew to the opposite end of the pond. Hooded mergansers can lift off with just a few running steps, unlike loons and even the common mergansers which are larger and heavier than hooded mergansers.

The other interesting observation was the absence of beavers. None of the beaver lodges showed signs of fresh mud and sticks, there were no winter food caches, and no freshly chewed sticks along the shore. In the thirteen years I have been monitoring Loon Pond, there have always been beavers living on it. I knew that there were at least two this summer in one small lodge, but they were not very active. I think they may have moved to a new pond or lake because of lack of food, since the beavers have cut down many of the shoreline deciduous trees, and also eaten a lot of the water lily roots that they need for winter forage.

If I don’t visit again soon, Loon Pond will be locked in with ice, and paddling will have to wait until next year. I hope that the banded loon pair had a safe migration to their wintering areas, and that they return again next year for a successful breeding season.

~E. George, ACLC Field Staff & Loon Naturalist Extraordinaire!

9/25/23: “Loon Pond,” NY - What’s up at loon pond?

Here is a summary of my three trips to Loon Pond. Since the nest was predated right before hatching, the loon pair is on vacation with no chicks to raise. They could visit other ponds and lakes or migrate to the ocean whenever they want, since they have no parental duties. However, staying on their territorial pond, as long as they have enough food, is not a bad plan. It is a safe place, and the loon pair can drive off any rivals who may drop in with designs of taking over this productive territory.

On August 1st, three loons were present: the loon pair and one intruder. The intruder was probably a female, since it spent more time interacting with the old territorial female than it did with the male. In the image below, you can see these three loons, and also notice that they are still in full breeding plumage of black and white.

A month later on September 8th, again an intruder was on the pond. This loon was very nervous and made frequent tremolo calls and spent most of its time avoiding the territorial pair. After a while it took flight. The female in the territorial pair, shown doing a wing flap the image on the left, has not started to molt yet.

On September 21st, only the territorial pair was present. The male made frequent low cooing calls to the female, almost like in spring before mating. The male is molting much more heavily now, and he looks ragged because he is losing his black feathers with their white spots. He will grow in a gray and white winter plumage, but he will retain his flight feathers for a few more months until January or February when he should be safely in a wintering area like the Atlantic Ocean. There he will be able to swim and dive but not need to fly for a couple of months until it is time to return to his breeding territory in the spring. The female is just starting to molt. Loons preen a lot when they are molting, and the surface of their lakes and ponds are speckled with floating loon feathers. Feathers wear out with use over time, and the tips become sparse, lacking the barbules that allow the loon to zip them back into shape and keep themselves waterproof. Also, the gray and white plumage is more camouflaged on the ocean where the loons have more predators and are no longer breeding.

Will the loon pair still be on Loon Pond the next time I visit? Will they stay as long as they did last year, when they also did not have a chick? In 2022, the female was gone by October 12, while the male stayed past October 23, but was gone by November 4. Time will tell.

~E. George, ACLC Field Staff & Loon Naturalist Extraordinaire!

7/18/23- “LooN Pond,” NY - Did the Eggs Hatch, and What Happened during the Loon Census?

The loon nest on the rock was due to hatch between July 2 and 7. I was excited to visit on July 7, hoping to see two little fuzzy dark chicks. Instead, I saw the two adults swimming together in the pond with no chicks on their backs. That was not a good sign.

I paddled toward the nest rock and could see that it was empty. Only one small piece of broken eggshell remained, and there were no eggs or eggshells in the water around the nest. Something had gotten the eggs and carried them off. Sadly, I went to retrieve the nest camera hoping that it would at least solve the mystery.

On July 15 I returned for the annual loon census. I had just a smidgeon of hope that the loons might try to renest because the female on Loon Pond has been an excellent re-nester after losing her first set of eggs. However, this year the loons had incubated almost to full term, and when that happens, they rarely renest.

Glassing the pond with binoculars, I spotted two loons in the middle. But wait, there were more! Four loons were doing a circle dance, swimming in a tight circle and looking at each other, checking one another out. I paddled out and joined the party. The banded territorial pair was there, but who were the other two? They acted like a pair, staying together when all four were not close, and both were unbanded. The loons swam together for 45 minutes, occasionally getting nervous, sinking low in the water and then splash diving and reappearing further away. But mostly they just swam around the pond together, looking at each other. The territorial male even preened and did a foot waggle, displaying his colored bands. That behavior indicates that he was relaxed and did not feel threatened by the intruding pair.

When I got home and checked the images on the camera, I was disappointed to see that the motion sensor had not been triggered by whatever got the eggs. Because I had to set the camera at some distance on a nearby island, it was only triggered by large moving objects like canoes, kayaks, and a beaver swimming past. It did tell me that the predation occurred on July 1, because the loons were photographed swimming right past the island, which they had not done during incubation, and they were not seen on the nest after that. A smaller mammal, like a mink, otter, or raccoon, must have snuck in from the far side and stolen the eggs.

At 8:30 the visiting pair took flight, circled the pond and headed in the direction of Nearby Pond. I thought they might have come from that pond and I knew that someone else was counting loons on Nearby Pond for the loon census. I would be able to contact them and determine if they saw two loons fly in and land soon after 8:30. I paddled all around the pond looking for signs of a new nest but did not find one.

A day later I contacted the Nearby Pond observer and was told that two loons had been present on the pond for the whole hour, and that no new loons had flown over or landed during that time. If the intruders were not from Nearby Pond, where did they come from? There are a few other ponds several miles away that may have loons, but no other ones in close proximity.

While it is extremely unlikely that the Loon Pond loons will re-nest, I will still hold a shard of hope for next week’s visit. If not, then they will have a summer vacation, fishing, resting, holding their territory from prospecting loons looking for a breeding pond, and getting ready for the autumn migration.

~E. George, ACLC Field Staff & Loon Naturalist Extraordinaire!

7/3/23- “Loon Pond”, NY - Visitors to the nest rock

You might think that incubation is very boring. The loon just sits on the eggs for hours on end. But the loon is usually alert, constantly monitoring the surroundings for threats, whether it be an eagle, a human, a raven, or another loon. I only visit the pond once a week for one to two hours, and yet I often witness a possible threat to the incubating loon or its eggs.

So it was these past two weeks, when I visited on 6/21 and again on 6/27. On 6/21, I found a truck already parked at the pond. As I paddled down the pond toward the nest, I encountered the female in the center of the pond. Suddenly the male pushed off the nest and wing-rowed toward the middle. He had obviously been spooked by something. Since he was off the nest, I paddled down to check to see if the eggs were still present and what had scared him. A small boat was in the far, shallow end near the nest, and when the guy in the boat saw me, he turned and rowed further away. He didn’t appear to have a fishing rod. The eggs looked okay, so I paddled back toward the middle of the pond where the loon pair was.

Then I heard a .22 gunshot, and then another, and I realized that the guy in the boat was probably hunting frogs. With binoculars I watched him reach a long-handled net and likely scoop up one of his victims. Yes, it is legal in New York State to hunt frogs so I couldn’t ask him to stop and leave the west shallow end, since that is where most of the bullfrogs and green frogs live. I just hoped that he would finish hunting and leave of his own accord, allowing the loons to get back on the nest. At least he had moved further from the nest, but the occasional gunshots with their startling noise might keep the loons off the nest.

On June 27 I visited Loon Pond again. I was happy to see several surviving bullfrogs basking on logs. I could see a loon on the nest from the opposite end of the pond, sitting upright in relaxed posture. But soon after I put my canoe in, the loon hunkered down in hangover position, indicating stress. Both loons are nervous incubators. I encountered the female fishing and preening in the middle of the pond, so the male was the one on the nest. Then I noticed a great blue heron hunting the shoreline, heading toward the loon nest. Would the heron bother the loon nest? What would the loon do when the heron got close?

I watched from a far distance, using binoculars and the telephoto lens of my camera. The heron slowly walked along the shore, once stabbing at prey in the water. It did not approach the nest rock but walked behind it, staying along the mainland shore. The loon stayed in hangover position and did not seem alarmed by the heron’s presence. The heron continued past the nest and was soon out of sight.

If all goes well, the eggs should hatch soon. Hopefully they have not been chilled or overheated from the loons being scared off the nest for too long. Who knows what other threats have occurred during all the time when I am not there to observe? The eggs will have to survive the July Fourth weekend, a time of increased human visitation and disturbance. Stay tuned to see if they do.

~E. George, ACLC Field Staff & Loon Naturalist Extraordinaire!

6/14/23- “Loon Pond”, NY - Nesting on a Rock

The banded pair of loons both returned to Loon Pond in April after the ice melted. The male arrived first, by 4/16, and the female had joined him by 4/20. She is at least 26 years old now and has been on Loon Pond every year since she was banded in 2002, and who knows how many years before that. Loons are usually five years old before they breed for the first time.

The black flies were pretty bad in many parts of the Adirondacks this spring, including Loon Pond. The loons spent much of their time diving, not just to catch fish but also to escape the biting flies. They waited to nest, possibly for the black flies to diminish. On June 8, an intruder loon was on the pond. The loon pair was searching for it, swimming around and craning their necks, and frequently peering underwater. One of the loons, probably the male, located the intruder and interacted with it, swimming close, while the two loons looked at each other and checked each other out. In the meantime, the other loon, the female, had disappeared. I spotted a black dot at the far southwest end of the pond. Could the loon be on a nest?

My binoculars revealed a loon on a nest on a large, partially vegetated rock, about the size of a bathtub. This was a new loon nest location for the Loon Pond loons, and a new one for me. I’ve seen loons nest on islands, bog mats, marshes, the mainland wooded shore, beaver lodges, and sandbars, but never a rock before now. I guess a rock is just a tiny island, after all. Meanwhile, the intruder loon ran across the water and took flight, leaving the pond and flying toward Nearby Pond.

I eased my canoe closer, knowing that I had to set up a nest camera and that I would probably flush the loon off the nest in order to do so. I approached very slowly and quietly because I didn’t want the loon to push off in a hurry and possibly kick an egg off the nest. The Loon Pond loons are average in their tolerance for humans, and do not usually allow close approach. The female eased gently into the water when I got too close for her comfort, and I could see two eggs on the nest, the usual number. I quickly set up the nest camera on a nearby island facing the nest, and paddled away fast so the loons could return to incubating. When I was far from the nest, I turned and spotted a loon climbing back on.

I returned on June 14 to monitor the pond. The female loon was fishing in the middle, diving frequently. I caught a glimpse of her orange band. The male was on the nest, but by the time I could see him, he was already in hangover position with his head and neck low, indicating stress, even though I was a third of the pond away. I took a quick distant photo with my telephoto lens, and paddled away, not wanting him to leave the nest. On my way back to shore, I noticed a snapping turtle on a beaver lodge, digging with powerful front legs trying to excavate a nest hole in the mud on the lodge.

Will the Loon Pond loons successfully incubate their two eggs and hatch two fluffy black chicks? Or will a predator find the nest and have loon eggs for lunch? If that happens, hopefully the nest camera will tell us who the predator was. Stay tuned for another update on Loon Pond. Loon eggs take 27-29 days to hatch, so there are only three weeks to go before the eggs might hatch!

~E. George, ACLC Field Staff & Loon Naturalist Extraordinaire!

5/2/23- “LOON POND”, NY - RETURN OF THE BANDED LOONS?

The first time I visit Loon Pond each spring, I am excited but apprehensive at the same time. I can’t wait to see the loons, but what if they haven’t returned? What if, instead of the two banded loons I have watched for years, there are two new, unbanded loons on the territory? Or no loons at all?

The ice was partly out by April 14, and all clear by the time I visited on April 16. I scanned with binoculars from shore and spotted one loon. Good! I paddled out and determined that it was the banded male loon, by seeing his white band on each leg. But there was no sign of the old female, who was first banded on Loon Pond in 2002 and had been breeding on it every year since then. That means that she would be at least 26 years old if she returned this year, since loons usually must be 5 years old before they breed for the first time, and she could be much older. Last year both loons were back on the pond by April 12, but the pond iced out a lot earlier in 2022.

Something about her behavior made me think it was the old female, but I couldn’t see her bands for quite a while. Both loons were fishing, and spending most of their time underwater, and in order to see leg bands you need the loon to be floating high in the water or have it lift a leg to preen or scratch or do a foot waggle. Finally, the loons paused from their diving, and I caught a flash of green from the left side of one loon. The old female has a blue band and a green band on her left leg, so I was pretty sure it was her, but I wanted a better look. I followed her longer and saw a flash of orange on the right leg. It had to be her, because she has an orange band with a black stripe plus a silver metal band on her right leg. Yay!

I watched the loons for some time and observed the female catch and eat a bullhead, a species of catfish with three sharp spines in its fins. Painted turtles were basking on logs in the shallow end of the pond, and a female common merganser shared a log as a resting place with several turtles.

From my limited observations of banded loons in my study area, it seems that more loons die over the winter or during migration, and don’t make it back to their breeding lakes, rather than dying during the time when they are back on their freshwater lakes. Adirondack loons spend 5 to 7 months in the Adirondacks, and the remainder on the ocean or on other bodies of water in between as stopovers during migration.

I visited again on April 20, figuring that if the female wasn’t back by then, she probably didn’t make it. I held my breath as I scanned the pond but couldn’t see any loons. I pushed off and paddled out where I had a better view of the pond and was thrilled to see two loons together. But was the other loon the old, banded female, or a new unbanded bird that took her place?

Returning on April 26, I found the banded loon pair fishing together in the deeper water. I caught a glimpse of the male’s two white bands, and the female even paused to preen and lifted her left leg, clearly showing me her blue and green bands. All was well. A mature great blue heron fished from a beaver lodge in the shallow end, and spring peepers sang. When and where will the loons nest this year? Will they hatch chicks? Will other loons visit and maybe fight to try to take over the territory? Stay tuned for more adventures of the loons at Loon Pond. I can’t wait to go back again.

~E. George, ACLC Field Staff & Loon Naturalist Extraordinaire!

12/15/22 - RESCUE ON FIRST LAKE, HERKIMER COUNTY, NY

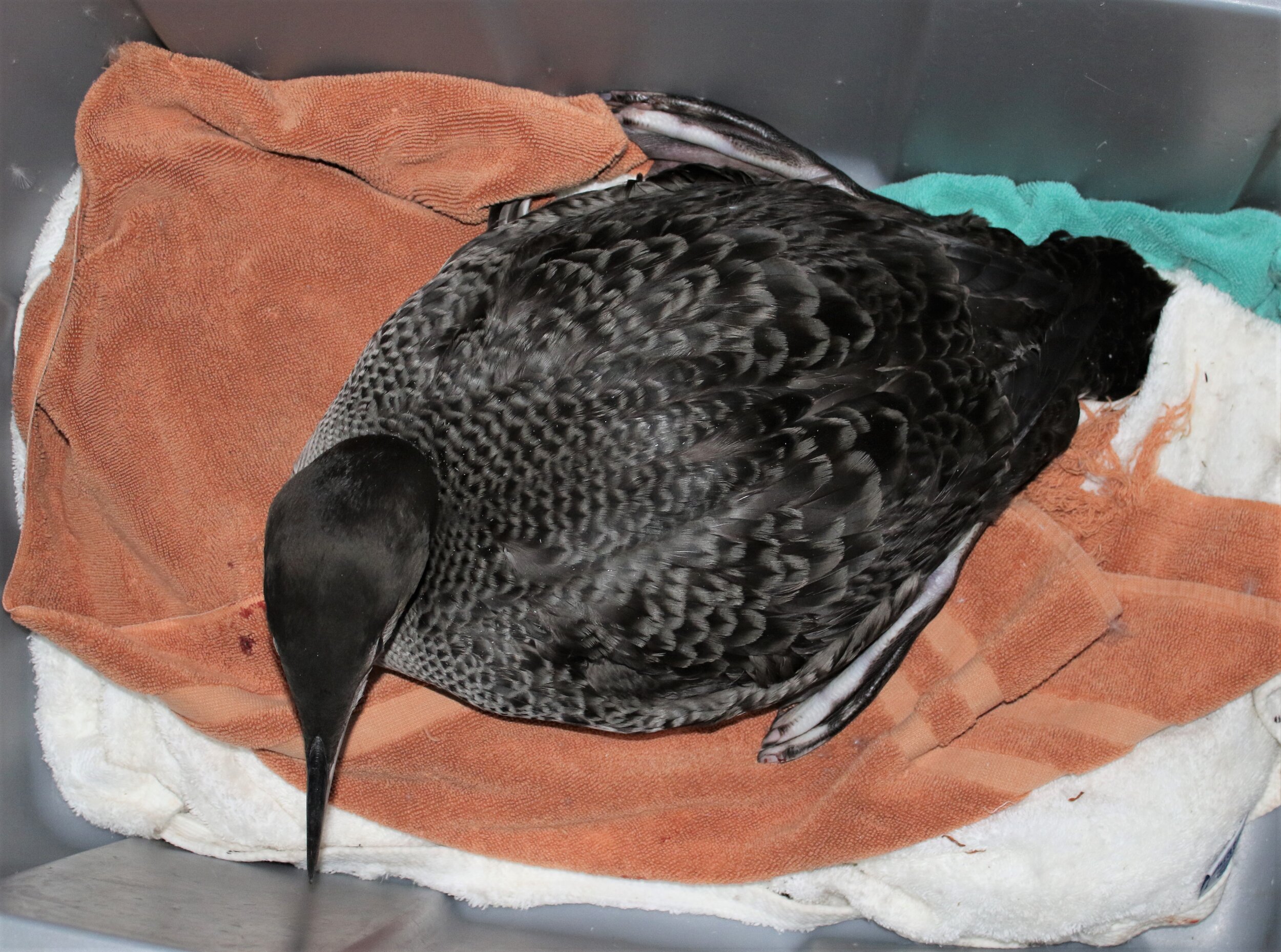

On Wednesday, December 14 the Adirondack Center for Loon Conservation received a report of an iced-in Common Loon on First Lake in the Town of Webb. Overnight the water froze further and the ice surrounding the loon thickened. While these changes might seem bad for the loon, the cold night made conditions safe for a rescue effort.

On Thursday, December 15, volunteers and staff from the Adirondack Center for Loon Conservation went to rescue the loon early in the morning. The group included Cody Sears, Jay Locke, Gary Lee, Don Andrews, and Kurt Gardner.

The loon was stuck in a small patch of open water about half a football field from shore. After carefully trekking across the ice, the rescuers attempted to extract the loon using a canoe and large net. The loon stayed free by diving quickly underwater, so the team switched up their tactics. Using a gill net to cover part of the hole in the ice and the canoe in unison, the loon was finally captured!

It was a healthy juvenile that was subsequently released to a larger ice-free lake to get another chance at successful migration. The Adirondack Center for Loon Conservation is very grateful for the hard work of the rescue team. Good work guys!

If you see an iced-in loon, please report it by calling (518)354-8636 or emailing info@adkloon.org.

~Jennifer Denny, ACLC Communications Coordinator

11/23/22 - “Loon Pond”, NY - Hard Water

Surprisingly, the male loon was still on Loon Pond on October 23. He stayed later this year without a chick than he did last year when he had a chick to feed and protect. However, on November 4 there were no loons on the pond. Both common and hooded mergansers were present, migrating through the area and stopping to feed on the fish, crayfish, and other aquatic invertebrates. Every autumn, Loon Pond turns into Merganser Pond after the loons leave and the mergansers stop by. Up to 50 mergansers might be present, with each species flocking up separately. Hooded mergansers do breed on Loon Pond, and each summer there is at least one family of hoodeds growing up. But the larger common mergansers tend to be just spring and fall visitors.

On November 4 one great blue heron was fishing the shallow west end. Just before dark the beavers emerged from their lodge to feed. November 19 was much colder with snow on the ground, and the beavers were active all afternoon. One of the adults was feeding on water lily roots, while another adult carried a big mouthful of grasses in its mouth to use for bedding in the lodge. A third adult beaver was eating twigs it had cut, while a beaver kit fed on small twigs from the winter food supply that the adults were caching in front of the lodge. A flock of hooded mergansers fed together in the shallows, and one of them caught something big that might have been a frog. About 25 hoodies, mostly females and immatures, were fishing throughout the pond, while four common mergansers worked the east end.

After two very cold days on November 20 and 21 when the temperature might not have gone above freezing, the forecast was for milder weather by midweek. I had hoped to paddle the pond one more time on November 23, but on the afternoon of November 21, I received a text with a photo that said, “Change of state.” A friend who lives near Loon Pond sent a picture of the pond, completely covered with ice. Unless the wind and warmer weather break up the skim of ice, life will go on under the surface, but the ducks, loons, and canoeists will have to wait until next year.

~E. George, ACLC Field Staff & Loon Naturalist Extraordinaire!

10/17/22 - “Loon Pond”, NY - Anybody Left on Loon Pond?

On October 5th, I paddled Loon Pond to see if the territorial pair of loons were still there. They were! Both were molting into winter plumage, and the male was much whiter and grayer than the female. Even the beaks and legs of loons turn gray in autumn, and you can see the loss of black pigment at the base of the bills of both loons. The loons were still making low cooing sounds to each other.

October 12 brought silence to the pond. The female loon was gone, and only the male remained. He looked more gray and white than a week ago, and spent his time fishing, diving and swimming underwater across the pond repeatedly.

The male was still there on October 16, along with a kingfisher, drake wood duck, and female hooded merganser. When the loon pair was together on the pond, they were reasonably approachable, and used to my presence. But the last two visits with the female gone, the male kept his distance and did not allow me to approach as close as usual before diving. I did manage to see the white band on his right leg, so I know it is the territorial male, and not another loon just visiting the pond.

Last year the loons had a chick, and the male stayed on the pond with the chick until some time between October 17 and October 21. I was surprised that the male was still there on the 16th this year, since he does not have a chick to defend and feed. I thought that loons would leave their territorial ponds to begin migration or staging sooner if they did not have a chick, but this guy, with no chick this year, is right on schedule like last year. Will he be on Loon Pond the next time I visit? I am guessing that he will be gone.

The female actually stayed longer this year with no chick than she did last year when she had a chick to care for. Last year she was gone by September 26, while this year she left between October 5th and 12th. This is not a huge difference, but an interesting observation. Maybe loons leave earlier when they have chicks constantly pestering them to be fed. We would need a lot more data to determine the relationship between when adults leave their ponds and lakes in autumn and the presence or absence of chicks, but since we end our loon monitoring season in mid-August, the ACLC does not get information on this.

Loon Pond is a wild and fascinating place to visit all year, even when the loons leave. I watched a beaver feeding on roots of shoreline grasses. A barred owl hooted before dark. And just as I was tying my canoe on the car to leave, a glorious coyote chorus erupted from close by, with at least four voices, including the high howls and yips of pups.

~E. George, ACLC Field Staff & Loon Naturalist Extraordinaire!

9/15/22 - “Loon Pond”, NY - Finally, the Incubation Ends

On September 6th I visited Loon Pond to see if the loons were still incubating their overdue egg from their second nesting attempt. I scanned with binoculars to the far west end, but no loon was on the nest. Then I spotted three adult loons swimming together, so I paddled down to the nest. The egg was still there, but was it still being incubated? On September 1st, no loon had been on the nest when I arrived, but the nest and egg were much warmer than the air temperature.

I felt the nest: cold. Then I picked up the egg: also, cold. It was obvious that the loons had finally given up their marathon incubation attempt, which was good since the egg should have hatched many days ago if it was viable. The loon pair could now relax, fish, and fatten up before migration. It was also time to start molting breeding plumage and grow in gray and white winter plumage, which requires a lot of energy. I picked up the egg and sniffed it—STINKY, another sign that the egg was certainly dead. But the egg was still intact, with no cracks or chips. Think how many times the loons climbed off the egg and climbed back on, turned it with their beaks, and sat down on it to incubate. For at least 53 days they exchanged places on the nest several times a day, and never cracked the egg. Also, no predators found the egg during that long time period. I collected the egg, careful not to crack it and create a stink bomb in my canoe and took it home to freeze it and bring it to the ACLC so they can have it tested for mercury contamination.

While I was at the nest, I heard the loons hoot and saw them look up. Another loon came flying in and landed on the pond. I started to paddle toward the four loons when they hooted again, and in came a fifth loon. In late August and September, loons become more social and get together in what I call “loon parties”. They swim together, circle, dive, but do not usually penguin dance or do wing-row chases because their hormones, aggression, and territoriality are diminishing. In winter loons are quite social and swim and fish together, often in large flocks on the ocean.

The five loons got along fairly well and cruised the pond together. The banded male loon held up a leg to shake off the water before tucking it under a wing, and I was able to see the bands. Suddenly one loon got nervous and wing-rowed away from the rest, making tremolos as it sped away. Later it reunited with the group, and all five loons were still on the pond when I left.

Soon the loon pair will leave the pond, maybe just for a few hours or more, and then to start their migration. Since they have no chick this year, there is nothing to keep them on the pond any longer, should they wish to leave.

Will the loon pair still be on Loon Pond the next time I visit? And what will the nest camera show, after 53 days of spying on the nest? Stay tuned for at least one more trip to Loon Pond for 2022.

~E. George, ACLC Field Staff & Loon Naturalist Extraordinaire!

9/9/22 - Rescue at Palmer Pond Dam - Essex County, NY

Last week, two juvenile Common Loons were found below the dam at Palmer Pond in Essex County, NY. When we arrived, they were swimming calmly downstream from the whitewater coming off the high dam. Ironically, they were just above a section of the stream where we had rescued an adult loon earlier this summer. Due to the fast water, tall dam, and steep banks, the young loons were trapped and unable to get themselves back to the lake above. Since loons are very heavy and have a unique anatomy, they need long stretches of open water to get airborne. The two young siblings at Palmer Pond were new to the art of flying, and had no hope of taking off from the stream.

Our rescue team, including three staff members from the Adirondack Center for Loon Conservation and five of our volunteers, gathered along the two sides of Palmer Pond’s outlet. We used a variety of nets and techniques to capture the loons. One was quickly caught after we began our effort. However, the other bird evaded rescuers with swift dives and impressive agility, until we employed a system involving two gill nets. This worked very well, and we finally captured the loon after a couple of tries.

We took the juveniles to a different lake nearby for release, since they were old enough to feed themselves and no longer required care from their parents. If we had returned them to Palmer Pond, we feared they may go back over the dam again!

We banded, weighed, and measured the loons before releasing them at their new home. Once again free, they looked delighted to be able to swim easily on the calm, flat water. The siblings swam away from shore together to inspect their new lake. Hopefully they will soon begin fattening up to prepare for migration.

The Adirondack Center for Loon Conservation thanks Ellie George, Gary Lee, Sue and Lance Durfey, Trish Pielnik, Larry McGory, and Kevin Boyle for their excellent help with this unique multi-loon rescue.

- Jen Denny, Communications-Education Coordinator

9/7/22 - “Loon Pond”, NY - September Incubation

An evening visit to Loon Pond on August 28 found the female still on the nest, while the male was floating on the pond. After a while, the female slid off the nest for a break, and swam out to meet her mate. The loons made low cooing calls to each other, and both preened a little, showing their leg bands. The low angled evening sun made their feathers glow.

Suddenly both loons started to tremolo, the “laughing” call of the loon which actually expresses stress or alarm. I scanned the skies looking for an eagle or an airplane but saw nothing. No bear or coyote appeared on shore, either. After a few minutes they stopped calling, and they swam slowly back towards the nest. By the time I was hauling my gear up the shore, I could just see a loon back on the nest.

On September first I visited Loon Pond in the morning. Both loons were swimming together in the southwest end, so I figured they had finally stopped incubating their overdue egg. I paddled to the nest and noticed the egg still there. I unlocked the nest camera and took it down, since the loons were at the far east end by now and wouldn’t be disturbed by me near their nest. Then I approached the nest, planning on collecting the egg if it was cold and abandoned, because the ACLC tests abandoned eggs for mercury levels. I reached out, putting my hand on the nest to brace myself so I wouldn’t tip the canoe over. The nest felt warm, even though it had been in the mid-40’s that night and was still only 50 degrees F. I picked up the egg, and it felt like holding a warm coffee mug in my hand. The loons were obviously still incubating and must have left the nest just before I arrived. I set the egg down gently and paddled away.

Some sharp hoot calls attracted my attention as I paddled toward the loon pair, and I spotted a third loon flying toward them, dropping swiftly toward the pond, feet out to slow the descent. The new loon zoomed right past me and dragged its feet on the water as brakes, then its tail, then its whole belly slid along the water until it stopped, in classic loon fashion. This unbanded loon visitor swam toward the Loon Pond pair, and all three interacted, swimming in a circle, diving together, and checking each other out. I watched for a while and then left, and the loons still had not gotten back on the nest by the time I drove away, but were still swimming with the visiting loon.

However, the loons had made it to September, still incubating their egg from their second nesting. That has to be a new record for late incubation. I plan to go back soon to see if they are still incubating, and if not, to collect the egg for analysis. There are also almost 1200 photos on the nest camera to scan through to see what kinds of creatures and weather threats beset the loons on the nest. Have you ever read Dr. Seuss’s book, “Horton Hatches the Egg”? It is beginning to feel like that at Loon Pond. Just how long will these loons incubate? I just wish that their egg could have hatched like Horton’s finally does.

~E. George, ACLC Field Staff & Loon Naturalist Extraordinaire!

8/23/22 - “Loon Pond”, NY - Going for the Record at Loon Pond

I could see a black head way down at the end of Loon Pond from the put-in spot. A loon was still on the nest, and it was August 21. Their one egg was due to hatch by August 10, so I know for sure that the egg is inviable. But the loons don’t know that. They are programmed to sit on their egg until it either hatches are gets predated or flooded. This is extremely late in the summer for a loon to be incubating and might be a new record for late incubation.

The fact that the loon pair still has high enough hormone levels to incubate is a testament to their good health. Most loons by now are responding to the decreasing daylight, getting less aggressive and more social, and will soon be molting their breeding plumage to be replaced by gray and white winter plumage. Some loons have even left their territories and are visiting other lakes and ponds on a regular basis. The loon pair from Nearby Pond was not on their pond when I checked a couple of times this past week, and there were no intruder loons on Loon Pond this past week, either, which reinforces that they are probably the main intruders who visit Loon Pond.

The male loon is usually the bird on the nest when I visit in early morning. The female is often resting, preening, or fishing. On August 12 there were still 3 intruders interacting with the Loon Pond pair, but I have seen none since then. However, the other residents of the pond go about their lives. The beavers are building a new lodge in the west end, and I watched one climb on shore and groom himself. A triplet of otter pups was exploring the pond one morning. Kingfishers, great blue herons, and young hooded mergansers all fish the shallows.

The Loon Pond loons have been very successful breeders. The old female is one of the most productive loons in the Adirondack Center for Loon Conservation’s long-term study. Her current mate of the last five years has fledged two chicks in 2019, two chicks in 2020, and one in 2021. You might remember that last year only one of the two eggs hatched, so having an inviable egg is not uncommon. Sometimes the egg has a genetic defect that causes it to not develop properly, or it may die during incubation if it gets chilled, overheated, or flooded.

I will continue to visit Loon Pond, even though our official loon monitoring season has just ended. I want to know how long the loons will persevere incubating the egg, and when they will leave for migration. And those loons just might set a record for the latest date that a loon has been incubating in the Adirondacks.

~E. George, ACLC Field Staff & Loon Naturalist Extraordinaire!

8/16/22 - “Loon Pond”, NY - OverDue

I have been visiting the pond almost every day for a week, hoping to find a newly hatched chick. I first found the egg in the nest the morning of July 11, and there was no nest on July 3, so the egg had to have been laid some time in between. Loon eggs normally take 27-29 days to hatch. If the egg was laid at the latest date possible, early morning on July 11, then by August 10, thirty days have passed, and the egg should have hatched. It is remotely possible that the male was sitting with a one-day old chick under him, but he did not act like he had any life underneath, nor was the female fishing for tiny fish and insect larvae to feed a chick.

Loons will often keep incubating for days and even weeks after an egg has died. They do not know that it is nonviable, and only know to keep sitting on it until it hatches, or gets predated, flooded, or the water level drops so much that the loon cannot climb up onto the nest. I once had a loon incubate an egg for 54 days on a different pond, and finally one day I came, and the nest was empty. Either it got predated so the loons stopped incubating, or they stopped incubating and then an animal had easier access to the egg. In the case of the Loon Pond loons, since this is very late in the season, their hormone levels will change with decreasing daylength, and they may stop incubating because their bodies tell them that breeding season is over.

The most probable cause of the egg not hatching is that it has been left exposed for an hour or more at a time on a number of mornings due to intrusions by other loons. On several occasions I have found 2 and even 3 other loons on Loon Pond in the early morning, and the parent loons leave the nest to interact with them. A breeding territory is the most important thing a loon owns, and they will do almost anything to defend it, sometimes fighting to the death.

None of the interactions I observed were violent, but there was circle dancing, splash diving, and the occasional penguin dance by both the male and female Loon Pond loons. In all cases the intruders eventually flew away, but sometimes after an hour and a half. Often the female loon would take flight after the intruders left, but she would return in five minutes or so. None of the intruders were banded, but it is likely that two of them were the residents from Nearby Pond. In August it is common for loons without chicks to fly to other ponds to check out territories and also just to socialize. As hormone levels drop, loons become more social prior to migration, and they can be highly social in autumn and winter when they often fish together in large flocks.

Not having a late chick can be a benefit for the Loon Pond loons. If they had an August chick, they would be feeding and defending it for the next 10 weeks, late into October. Autumn is a time when loons need to eat a lot because they start to molt all their feathers except for their flight feathers, and that takes a lot of protein to grow in new plumage. Also, they need to store fat so they can fuel their migratory flight.

I shall continue to hold out just a smidgeon of hope that a chick is hiding under the father’s wings on the nest. But I am already feeling sad, and the song by Danny O’Keefe is running through my head:

“ Some gotta win, some gotta lose.

Good time Charlie’s got the blues.”

~E. George, ACLC Field Staff & Loon Naturalist Extraordinaire!

7/30/22 - “Loon Pond”, NY - One Week to Go, But. . .

The loons started their second nest some time between July 4 and July 10, so the chick could hatch any time from August 1 through August 9, since it takes 27 to 29 days for an egg to develop fully and hatch. The loons have endured several threats and challenges already during this second incubation.

On July 11 they had two intruder loons to chase away. On July 16, during the Annual Loon Census, a photographer was already on the pond in a kayak when I arrived, he was too close to the loons, and they were wailing and swimming away. He told me that two other loons had been on the pond earlier in the morning, and they had just flown off. The photographer left, and soon both banded loons flew off the pond, too. I figured the nest must have been predated for both loons to leave, so I paddled down and discovered that the egg was still in the nest and looked intact. The female loon soon returned, and after another 15 minutes, so did the male. Then the female slowly swam to the west end and got on the nest, but neither loon had been on the nest for over an hour, and probably longer. Hopefully the egg did not suffer, since it was a warm morning.

On July 19, the female was on the nest while the male swam in the west end of the pond. All was calm for a change. The following week was brutally hot, and I feared that the loons might abandon incubating because they are large birds with a lot of black plumage and they can overheat on land. When it is hot, they open their mouths and breath harder to cool off through evaporation, and that helps but not always enough. They can and do take breaks where they get off the nest and swim, dive, and stretch before returning.

On July 27, the female was resting and preening in the middle of the pond, while the male was on the nest. He was already in hangover position, indicating stress, when I was only halfway across the pond, so I didn’t go any closer. I paddled instead toward a beaver lodge and saw a brown body in the water. Beaver or otter? A brown head swam straight toward me, and I could see that it was an adult otter, maybe the mother otter who has raised pups the last two years, often spending a week or more at Loon Pond. The wind was in my face so she couldn’t smell me, and she swam quite close before she sensed something was amiss and rose up like a periscope in the water. She stared at me for a few seconds, then slid silently back into the water and disappeared.

I love otters, but otters sometimes prey on loon eggs and it is possible that she was the predator who found the first loon nest. Will she find the second nest and have a loon egg for lunch, or will the loon nest escape notice for another week and hatch an August chick? Cross your fingers for the loons, and check back in a few days to find out!

~E. George, ACLC Field Staff & Loon Naturalist Extraordinaire!

7/19/22 - “LOON POND”, NY - NEver Give Up

The loon pair had lost their first nest to predation by June 26. By July 3, there was still no sign of a second nest, and the season was getting late for loon nesting. I arrived at Loon Pond on July 11, still hopeful that the old female might have attempted a renest. When I looked out over the pond, I saw four loons interacting, and my heart sank. The banded loon pair was circling on the water with another unbanded pair of loons, possibly the territorial pair from Nearby Pond. Soon one of the intruders took flight, immediately followed by the other. But then I was surprised to see the Loon Pond female and then the male run across the water to fly down to the far west end of the pond.

Why would they be in such a hurry, since they had already driven off their rivals? Could they have a new nest down there? I paddled west and hung offshore some distance out, watching the loons to see if they might give me a clue. One loon disappeared, and I watched the shore for signs of a loon climbing onto a nest. Not seeing anything, I paddled a little closer, and suddenly spotted a black beak sticking out from the high marsh grass on one of the islands. Aha! A second nest!

Meanwhile, the male loon took flight and left the pond. A few minutes later the female on the nest pushed off into the water and started to tremolo, a call that means she is distressed, and that danger is probably near. Scanning the sky, I spotted an immature bald eagle, which flew close to the nest and landed in a tree along the shore. It was watching the loon and also looked toward the nest. Oh, no! What if it gets the egg? I paddled to the nest, hoping that my presence would keep the eagle away from it. I saw the one olive-brown egg speckled with black nestled in the grassy bowl the loons had built. Finally, the eagle flew across the pond and landed in a tree further away, so I paddled away and the female swam back to the nest and climbed back on.

Whew! A loon’s life is not boring but instead is filled with challenges. I returned later in the day and set up the nest camera on an uprooted tree in the water. Due to the tall grass, the nest itself is obscured from view, but if a large predator like a bear, coyote, or a human were bothering the nest, the camera should be able to photograph that. The original nest was on private land, so I did not set up the camera there because I did not have permission and the owners were not present to ask.

This second nest is a testament to the health and viability of the loon parents, especially the old female. She had to have high enough hormone levels to go through another reproductive cycle, and also had to have enough body condition and energy to produce another egg. Loon eggs are large and contain a lot of protein and fat that the female had to draw from her own body.

The Loon Pond female has been the queen of the renest, having done it many times in the 12 years I have observed the pond. About 7 years ago she had a late second nest that hatched its one egg in the first week of August, and this chick was successfully raised and fledged. If this year’s renest is fully incubated, the egg should hatch in early August, too. Let’s hope for the best, and never give up like the Loon Pond loons!

~E. George, ACLC Field Staff & Loon Naturalist Extraordinaire!

7/13/22 - “Loon Pond”, NY - Loon Pond CSI: Who Dunnit?

The loon nest on the mainland had been incubated for about two weeks when I arrived on June 26. Right away I suspected something was wrong, because both loons were in the middle of the pond together, fishing. One of them should have been on the nest. I paddled toward the nest with a sinking feeling in my stomach. No eggs were in the nest, no eggshells, nothing. Something had gotten the eggs and carried them off. I looked in the water at the edge of the nest and scanned the marshy shoreline with my eyes but couldn’t find any hint of an egg.

Common loon egg predators include ravens, eagles, raccoons, otters, mink, and even bears and coyotes. Since this nest was on the mainland and not on an island this year, it was more accessible to land predators. But it was still early enough for the loons to renest, and the Loon Pond female has a long history of renesting when she loses her first nest. However, renesting is more likely if the nest is lost after only a week or less. The longer the loons incubate, the less likely they are to make a second nest if the first one is lost.

On the third of July I returned, hopeful that I might find a second nest. But the sight of the two loons swimming together in the pond sunk my hopes. I paddled around all the islands and shoreline just in case and went back to the original nest to check it again. It was still empty and didn’t show any signs of the loons adding any new nest material. Usually when loons lose a nest, they will nest somewhere different the second time. Then I caught a glimpse of something olive-gray in the marsh grass behind the nest. Could it be one of the stolen eggs?

I got out of the canoe and spotted both eggs in the marsh grass about four to five feet behind the nest but hidden from view from the pond due to the high grasses. The eggs had one end broken open, large eggshell pieces were strewn about, and the eggs were empty. Who had eaten these eggs?

A raven or gull or eagle would have pecked a hole in the egg and eaten the contents, probably right in the nest, although an eagle could carry an egg away. A bear or coyote would have jaws large enough to crush the egg so the large half eggshells probably would have been broken up. That leaves raccoon, mink, or otter, or possibly fox, as the potential predator. The animal carried each egg back toward slightly drier land and ate them, not carrying them very far. This creature was not being bad, or a villain, but was just hunting for food for itself and maybe its young. While it is sad that the eggs were not able to hatch, it is just a natural part of the food web. I have eaten quite a few eggs in my lifetime, and I’ll bet you have, too.

While it is late in the year for a loon to nest, it is still possible. There is just enough time left for a loon to lay an egg, incubate for 27-29 days, and raise its chick to 12 weeks of age when it would be independent and could fly before the pond freezes over. Once on Loon Pond there was a second nest that hatched the first week in August, and the chick did fledge and fly off the pond. And one year, the Loon Pond female made four nests, probably a record for loons, and each time a predator, likely a mink that year, got the single egg. Loons usually wait a week or more after losing a nest before they make a second nest, and enough time has passed since the nest was predated for the loons to nest again.

I will hold my breathe the next time I visit Loon Pond and hope to find a second nest being incubated. It’s not likely, but it is possible.

~E. George, ACLC Field Staff & Loon Naturalist Extraordinaire!

6/24/22 - “Loon Pond”, NY - On the Nest

The Loon Pond loons are nesting! Weekly visits to monitor the loons started at the end of May. At first, the banded pair were avoiding the always abundant blackflies, staying low in the water, wiping their heads on their backs, and diving frequently. But the numbers of blackflies dropped as June progressed, and some time between June 8 and June 12, the loons built a nest of grasses along the mainland. This is the first time in the 12 years that I have monitored the pond that the loons have not nested on one of the islands, but instead are using the mainland. The mainland has more risks for nesting, since raccoons, bears, and other mammalian predators can find the nest more easily.

The male loon pushed gently off the nest to take a break in the water and the two eggs were visible. They have more dark markings on the shell than most loon eggs do. The male and female swam together for a few minutes, and then the female returned to the nest. She stood up and turned the eggs before settling down to incubate.

Will two chicks hatch from this nest? Stay tuned to find out.

~E. George, ACLC Field Staff & Loon Naturalist Extraordinaire!

4/20/22 - “Loon Pond”, NY - Twenty Years on Loon Pond

The ice went out on Loon Pond on April 10-11 this year, and I paddled it on April 12th. The first time I paddle one of the ponds that I monitor for loons, I am very excited and a little worried to discover if the banded loons have returned. Are they back yet? Did they survive migration and wintering on the ocean? Will there be a new mate or a new pair altogether?

I always root for the banded loons to return, because I get to know them as individuals and care about them deeply. The more years a loon returns to the same pond or lake, the more experienced it becomes at finding food, choosing nest sites, incubating, and raising chicks.

I started paddling, scanning the shoreline with binoculars. I didn’t spot any loons for several minutes, but then I saw a flash of white and found a loon pair in the far west end. I sprinted down there, slowing as I neared the loons. They acted like a bonded pair; swimming fairly close to each other. The larger loon, the male, was making a low hoot call about once every minute. I noticed a flash of white on one of the male’s legs and knew then that he was probably the returning territorial male who was banded in 2019. I later confirmed this when I saw his other bands, white over silver on the right leg and white over blue on the left.

The female of the pair was harder to see bands on because she floated a bit lower in the water. I was most interested in her, because in 2002 the territorial female was first banded on this pond, and had returned every year since then, raising chicks successfully most years. Last year she had raised one chick with the banded male. Was it the old Loon Pond female, or a new female? Finally, a flash of orange on her right leg told me it was the old gal, and as I followed and watched, I managed to see all of her bands, orange stripe over silver on the right leg, and blue over green on the left.

She is one of the older banded loons still alive in the ACLC’s study of breeding loons in the Adirondacks. Loons must be about 5 years old to breed, so the Loon Pond female had to be at least 5 when she was first banded as a breeding adult. That makes her at least 25 years old. She is also one of the most successful breeders, producing chicks during most years. I have been monitoring Loon Pond since 2010 and have watched her pair up with three different males during this time period, raising chicks with each of them.

I always get a warm feeling of gratitude when I find that a banded loon has returned to its breeding lake, especially the Loon Pond female. We humans have made many changes to the world and created a lot of challenges for the wild creatures with which we share the planet. But if a loon can fly from the Adirondacks to the ocean and back 20 times or more, finding places to land and feed and rest, then the earth still has hope.

~E. George, ACLC Field Staff & Loon Naturalist Extraordinaire!

3/6/2022 - Five Loons Rescued on Lake Champlain

Nordic ice skating at its extreme takes well equipped skaters on tours of tens of miles on variable and dangerous ice. Devotees of this sport learn to read and test ice; they wear dry suits and PFDs and carry safety equipment. On Saturday, Eric Teed, Kevin Boyle, Dan Spada and John Rosenthal were on a 20-plus-mile tour of Lake Champlain and came upon a small hole in the ice with five loons in it.

Common Loons migrate from their breeding grounds to open water for the winter. Ideally these birds go to the ocean, but sometimes they stop at Lake Champlain. In a mild winter this can be a good place for them. But in a year like this one when most of the lake freezes, it can be a loon’s demise.

In winter, loons molt their flight feathers and cannot fly. If the ice freezes suddenly they can be trapped. They can swim in circles to keep an area open, but if it is cold, the ice slowly closes in on them. Trapped, they can become easy prey for bald eagles and peregrine falcons.

Knowing this, Teed called Nina Schoch of the Adirondack Center for Loon Conservation from the ice. Schoch answered on the second ring, “Hi Eric”. Teed, “I’m on Champlain”. Schoch, “How many loons do you have?” Direct and to the point, a barrage of emails and phone calls followed, and a rescue plan was launched.

Cody Sears, the Center’s Wildlife Technician, would lead the rescue, Teed and Boyle on ice safety, and loon naturalist Ellie George handling the health check on birds once they were captured. Susan Harry and Jackie Miller, also with ACLC, rounded out a skeleton crew.

First thing Sunday morning from Fort Cassin Point at the mouth of Otter Creek, Teed was able to see through a spotting scope twelve bald eagles around the hole and only two loons. Maybe three were already gone. Boyle and Teed skated out the mile and a half for a closer look. The eagles dispersed and all five loons were still there. The other three had been diving to avoid predation.

Sears brought a canoe to be dragged across the ice, filled with nets and containers for the birds. On approach from a threat, loons will dive and resurface only for an instant to take a breath. A gill net draped over part of the hole entangles a bird that is quickly brought out on the ice, untangled, and placed in a box. Sears and Boyle got all five in short order.

Back on shore the loons were carefully inspected for any wounds or other injuries. One of the birds had been banded. It turns out that bird was twice lucky. It was rescued and banded by ACLC on Lake George last winter.

Thanks to Rosenthal of Charlotte, the team knew that open water and safety for the loons was just twelve miles north of the rescue site. The crew and canoe carrying the five loons were quickly back on the ice, this time at Charlotte Town Beach, where old ice on the inner bay was navigated to the edge and open water. The loons were released one at a time directly to the water.

The loons found each other again. They were in open water now, seen swimming together, with another chance to make it through the winter.

Boyle, who had never been closer to a loon than most people, worked ferociously with Sears, diving right in handling the birds. After the rescue, he said, “I don’t often get a chance to change the world.”

~ Eric Teed, Guest Contributor & Loon Rescuer

* A version of this article has been published in the Charlotte News.

2/12/22 - Stonington, CT - Band Resighting!

If you regularly read our Adirondack Loon Blog, this story will sound familiar to you, with an exciting new development!

To recap: On July 30, 2021, staff and volunteers from the ACLC rescued a juvenile loon from fishing line entanglement on Paradox Lake, NY. They freed the loon from the line, treated abrasions on its beak with betadine, gave it colored bands for identification, and released it back to the wild. They hoped it would successfully migrate in fall, but the young loon would likely have to overcome other potential threats in the mean-time, such as bald eagle attacks, lead fishing tackle ingestion, and of course, more discarded fishing line.

Juvenile loon on Paradox Lake, NY. Photo by E. George.

Common Loons migrate to open water and spend the winter there. We know that Adirondack loons generally travel to the Atlantic Coast, thanks to previous research and band resightings. It’s not often that we get to find out how one of our rescues has faired post-migration, but this year we did!

Juvenile loon resighted at Stonington Fishermen’s Dock. Photo by Scott Whalen.

The juvenile from Paradox Lake was was photographed on February 12, 2022 at the Stonington Fishermen’s Dock, in Stonington, CT. It was swimming with other loons, and was identified by the unique bands on its legs. When loon researchers saw the photo, they checked a database of banded loons for its unique band combination (right leg: orange stripe over red, left leg: silver over green). This combination led to just one individual, the Paradox Lake juvenile!

Juvenile loons spend a few years on the open water of the ocean after their initial migration. Since they are not yet mature enough to breed, there is no need to travel to more protected northern lakes and ponds in summer. This loon will return to the Adirondack region in a few years to start appraising territories and potential mates, but until then it will stay on the Atlantic ocean.

It was great to see you again, loon!

2/1/22 - Lake George, Warren County, NY

On Tuesday, February 1, the Adirondack Center for Loon Conservation was contacted by Jason Jordan, who was ice fishing with Tim Denno on Lake George. He reported a Common Loon on the ice near Hague Beach.

At first, the ACLC staff were surprised that another iced-in loon was being reported on the water body so soon, but considering how rapidly Lake George froze last week, it is not all that surprising! (Scroll down to see the details from the January 30 loon rescue). These loons must have missed the seasonal cues telling them to leave before they molted their flight feathers, and then got stuck as the ice rapidly closed in around them.

The anglers removed the loon from the ice to protect it from eagles and other potential dangers, then transferred it to staff from the Adirondack Center for Loon Conservation.

It is especially important to rescue adult loons when it is safe to do so. Common Loons may live 25-35 years and can return to breeding lakes many times, so each individual loon plays an important part in maintaining their population levels. It is very fortunate that fishermen noticed this loon (and the two loons on Sunday) before any harm was done.

Dr. Nina Schoch checked the loon for injuries, and again, found that the loon was healthy, and had only gotten stuck because it already molted its flight feathers. After banding and weighing it, the ACLC staff transported the loon to Lake Champlain.

Upon arrival at Lake Champlain, the loon was eager to return to open water. The staff wanted to find a better spot for the release, but the loon had other plans! It sprung from their hands and returned to the water with a splash!

If you’re ever out enjoying a frozen lake and see a loon on the ice, please give the Adirondack Center for Loon Conservation a call at (518)354-8636. The birds cannot get off on their own. The quick actions of ice anglers saved three loons this week!

1/30/22 - Lake George, Warren County, NY

On Sunday, January 30, Nick Weis and Mattie Riley went out ice fishing on Lake George near Pilot Knob. Their plans quickly changed when they heard a loon call from across the ice. While looking around for the source of the sound, Nick noticed two Common Loons sitting on the ice, being harassed by a Bald Eagle. He rushed across the ice and scared off the eagle, saving the helpless loons from certain death.

Since the loons did not even have a small pocket of water to dive, they hadn’t been able to eat. Nick kindly shared his ice fishing minnows with the hungry loons, then took them back to his shanty to keep them safe while he tried to contact someone who could help.

Nick communicated the situation to North Country Wild Care, who reached out to the Adirondack Center for Loon Conservation. Shortly after, Nick loaded the rescued loons into his car and met the ACLC staff in town.

Dr. Nina Schoch checked the rescued loons for injuries, and noticed that they were missing the feathers they would need to fly, called “flight feathers”. Among their drab brown winter plumage, their primary and secondary feathers had already molted. Dr. Schoch explained how this problem arises:

“Each year, loons need to migrate from their breeding lakes to open water prior to molting out their flight feathers, which they do in late-winter. They molt them all out at once, and so are flightless for a month or more until the flight feathers grow back.

However, if the lakes are still open in mid-winter, then they freeze suddenly after a steep drop in temperature, the loons may have missed the cue to migrate prior to molting. Thus, some loons get “iced-in” while they’re unable to fly.

We have seen an increasing trend in these cases of “molt-migration mismatch” as the climate in the Northeast warms, and the ice-in dates get later in the winter.”

The loons were adults, having either spent the summer on Lake George, or taken a break from migration there. They did not have any injuries, so after banding, weighing, rehydration and antibiotics (just in case the eagle had attempted an earlier attack), Dr. Schoch determined the loons to be fit for release.

The Adirondack Center for Loon Conservation staff took the loons to the shore of Lake Champlain, where the water is ice-free and the constant passage of ferries will keep an open lane. There, the loons will have time to regrow their flight feathers before continuing to migrate. Ellie George and Susan Harry released the birds safely into Lake Champlain. The photos below were taken by Cal George, ACLC volunteer.

Right now, the loon’s wings look particularly skinny and wispy, but soon they will bulk up with new flight feathers. Upon return to the water, the loons stretched and swam happily, seemingly relieved to have some open water and a second chance.

The Adirondack Center for Loon Conservation staff was thankful to the fishermen who acted quickly to save the loons. Reflecting on his participation in the rescue, Nick Weis said, “If anyone has ever been in the Adirondacks on the water, and had the pleasure to see or hear these birds, you’ll know how awesome they are and why they deserved a fair chance to live.”

12/31/21 - Star Lake, St. Lawrence County, NY

On Tuesday, December 28th, the Adirondack Center for Loon Conservation staff joined Star Lake Fire & Rescue in their efforts to save an iced-in loon. Star Lake residents initially noticed the loon on Christmas morning, swimming and diving in a small, open hole of water.

Common Loons are heavy birds that may need as much as 400 meters of open water to use as a runway to take off. The Star Lake loon became trapped as the area of open water got smaller. It would soon become vulnerable to predators, such as eagles, if not rescued.

The rescuers wore dry suits to protect them against the chilly water. Winter rescues must be carefully coordinated, since a risk is always present.

Loons can dive under the surface quickly, so it takes both skill and luck to get them in a net. Cody Sears, the ACLC’s Wildlife Technician, went out on the ice with these members of Star Lake Fire & Rescue: Mike Sovay, Chief Rick Rusaw, 1st Asst Chief Cory Daniels, 2nd Asst Chief Logan Hayes, Rescue Capt. Lynne Backus, and Ben Wood.

Using a large net, they were able to successfully capture the loon without incident and bring it to shore. After banding the loon, it was successfully released to the open water at Lake Champlain, where it will have ample “runway” to take off, fly, and continue its migration.

11/19/21 - “Loon Pond”, NY - Goodbye, Chick! Hello, Red-Throated Loon!

Juvenile Common Loon on Loon Pond.

November 12th was the last day I observed the Common Loon chick on the pond. It was at the end of the day after a rain, and the chick was quiet, just floating on the pond. It hooted to me softly and I returned the calls. I left after the sun set, and the chick, now considered to be a juvenile, was still on the pond.

On November 14th, the pond appeared to be loon-less. Then I caught a glimpse of a large gray and white bird on the water in the far west end, so I paddled down there fast hoping to see the chick one last time. But no, the bird was a juvenile Common Merganser, another species of fish-eating waterfowl that was passing through on migration. Both juvenile and female Common Mergansers have gray backs and white breasts like Common Loon juveniles and adults in winter plumage, but their heads are rusty red and the feathers on top stick out jaggedly like the bird is having a bad hair day. I was glad that the chick had probably migrated, but sad at the same time because I missed watching it.

Juvenile Common Merganser on Loon Pond.

I hiked into Nearby Pond and another pond close to Loon Pond to see if maybe the chick had flown there, but I did not see any loons on either pond, just a few Hooded Mergansers.

The next time I visited Loon Pond was November 17th. It was possible that the chick might have visited another local pond and returned to Loon Pond. I stood by the shore ice and scanned with binoculars. Aha! There was a bird way down in the west end, and it looked like a loon! But it didn’t look quite like the chick. It was smaller and had more white on it. It dove like a loon and resurfaced, and I knew I would be breaking the ice to put my canoe in and battle the waves to get a better look at this bird.

I had an exciting thought that the bird might be a Red-throated Loon, the smallest species of loon which breeds in the Arctic on small, shallow tundra ponds, bogs, and marshes. I had only seen a few of these over the years on Lake Champlain during spring or fall migration. I had never seen one on an Adirondack pond or lake, and I knew this would be a rare sighting if it really was one.

I broke the ice along the shore by cracking it with my boots, and made a slot for my canoe to slip in. Most of the pond was ice-free. I could see a beaver swimming along shore with a mouthful of saplings to carry to its food cache by the lodge. I decided to watch and photograph the beaver first before checking out the mystery bird, which by now I had decided was probably the juvenile Common Merganser that I had seen three days ago. It just couldn’t be a Red-throated Loon. Or could it?

The mystery bird was swimming my way, and after photographing the beaver I headed toward it. I looked with binoculars and my eyes got big and my mouth dropped open. It WAS a Red-throated Loon!! I started taking photos and gradually drifted closer to the loon. It swam at an angle toward me, maybe trying to check me out, too. I had never seen one up close, and the pattern of white markings on the gray feathers of its back was strikingly beautiful. I watched the loon dive several times, but I did not see it come up with a fish. Perhaps it ate them underwater if it caught any.

Suddenly the loon started to run across the water, and was flying very quickly, getting off the water with much less effort than a larger, heavier common loon would. It flew to the east end and glided down to the water, sliding on its belly like a Common Loon. The loon stayed in the east end for a while, diving and probably fishing. Then I saw it take flight again, heading west toward where I was. The loon turned when it got over me and circled back east. It flew eight laps above the pond, each time turning above me, getting higher and higher in the sky with each lap. I figured it was going to head south and continue its long journey, but after it reached the east end for the eighth time, it half folded its wings and dove steeply downward, leveling out before it got to the water and sliding on its belly for a landing. Maybe it was just checking out its surroundings way up there in the sky, or maybe it was getting ready to leave.

I paddled toward the loon again, and it swam past me, even closer than before. The Red-throated Loon has a very thin bill which it often holds tilted upward. It is a much more delicate-looking bird than a common loon, and this particular one was more active, swimming with faster leg strokes. I finally decided to leave the pond, with the loon still there, heading to the west end again.

This loon was an adult in winter plumage, and it had already migrated many miles from its breeding grounds in the Arctic. Red-throated Loons breed across northern Canada and Alaska. Their smaller size allows them to utilize smaller ponds and wetlands for nesting, since they can take flight from a much smaller body of water than other, larger species of loons. These loons have a red throat in breeding plumage with the rest of the head and neck solid gray, except that the back of the neck has vertical gray and white stripes.

Adult Red-throated Loon taking a break on Loon Pond during migration.

I hope that this loon stops on Loon Pond during its migration north next spring and that I may be privileged to see it in breeding plumage. Perhaps it will stop again next November when it heads to the ocean to spend the winter, as the Common Loon chick that hatched on Loon Pond is doing now.

Safe travels, all you migrating loons! The loon juveniles will stay on the ocean for three years or so before returning to their natal ponds as adults. But the adults that survive will head back north next April when they feel the urge, when they know deep inside that the ponds and lakes are thawing out, and it is time to breed again.

~E. George, ACLC Field Staff & Loon Naturalist Extraordinaire!

11/14/21 - “Loon Pond”, NY - Practicing for the Big Flight